The Mind of the Church

A catechetical lecture on acquiring a Christian worldview and navigating common convert pitfalls

In Fall 2024 I developed a fourteen-part catechetical program with the blessing and guidance of our parish priest. The below article served as both the basis for the second catechetical lecture and was provided as a handout for the catechumens to take home and read—with further study resources provided according to an approved reading list blessed by our rector.

As Fr. Peter Heers, echoing the Holy Fathers themselves, has said: Catechism is purification. The aim of our “program” was, then, to teach them what it looks like to live an Orthodox Christian life in humility and the fear of God.

Let the inquirer/catechumen who comes across this series of catechetical lectures understand that this is the least important part of their formation. Above all, they must be in a parish. There is no way to Christ other than being in a canonical Orthodox Christian Church.

The Mind of the Church

Our society today has adopted a hyper-materialistic view of the world. For most of society, the very notion that there is a God is little more than a silly superstition, made obsolete by the advancements of science. Those who do believe in God are told they must compartmentalize their faith, relegating it only to Sunday, and only to things pertaining to their faith. This is impossible, and as a result, they import their secular worldview—the suppositions and principles which guide the other six days of their week—permeates their faith. This is why Americans see religion as a personal matter, a matter of personal interpretation, able to be modified to fit the prevailing winds of popular culture.

This makes true faith impossible, and turns Christianity into little more than a feel-good self-help program. Unfortunately, even when we see the flaws in this way of thinking, even when we come to the determination that the Orthodox Church is the Church which Christ established, the Apostles preached, the Martyrs died for, and the Fathers preserved, we bring this ideological baggage with us into the Church.

Unfortunately, many will never rid themselves of the secular ideologies which form the foundation of their worldview. As a result, they never truly become Orthodox. To become Orthodox, to truly live an Orthodox life, we must think like an Orthodox Christian. Our faith cannot be compartmentalized, but must permeate all we think, do, and say—it must be the very air we breathe. We must shed our secular way of looking at the world and adopt an Orthodox Worldview, or the Mind of the Church. By doing so, we can come to truly understand who Christ is, what He requires of us and how we can be saved even today in these latter times.

What is Orthodoxy?

The simple answer is that Orthodoxy means Right Belief (Ορθο: right, correctness of; δοξία: doctrine, belief). The Church established by Christ and His Apostles was always said to be Orthodox, ie., the correct, right-believing Church—opposed to the sectarian and heretical groups which sprung up even in Apostolic times.

Orthodoxy is an experience of God within the community which He established on the earth—a community which, in Him, transcends space and time. The Church is not a loosely affiliated organization of individuals who more or less believe the same thing; it is the extension of the incarnation, entering into which we come into contact with the right belief and worship of God directly. Our forefathers in the Russian Church understood this clearly when they translated Orthodoxy as Pravoslavie (Православие), meaning Right Glorification. In doing so, they showed that the living expression of faith, in liturgy and doxology, defined the faith in themselves.

The worship of the Church is composed of interlocking cycles of personal and communal prayers, and in these the Church enters into Sacred History while simultaneously setting apart and sanctifying the hours, days, weeks, and years as it moves through time and space towards the fulfilment of all things in Christ—redeeming the days. By entering into the life of the Church, we enter into this timeless experience of God and our lives sanctified by the right knowledge and glorification of the Holy Trinity.

“Your survival as an Orthodox Christian will depend very much on your contact with the living tradition of Orthodoxy. This is something you won’t get in books.” —Fr. Seraphim Rose

“I am the Way, the Truth, and the Life.” —John 14:6

The right belief of the Church allows us to properly know who God is, to know He who is Truth itself. Likewise, right glorification allows us to worship God in spirit and in truth and commune with Him—He who is Life itself. If Jesus Christ, the Logos of God, is the way, the truth, and the life [Jn 14:6] and the Church is the Body of Christ [Rom 12:4-5; Col. 12:12; 1 Cor. 12:12&27], then it is (as the Apostle Paul states) the Pillar and Ground of Truth [1 Tim. 3:15]; it is the Way to Him.

From this we can draw a few conclusions:

- Truth is not an abstract concept, much less something subjectively determined by the individual through sense data and deductive reasoning (which are themselves fallen), but a Person: Jesus Christ, the Logos of God.

- If Truth is a person and not merely an abstraction, then it must be sought and known by the heart, not the mind (alone).

- Anything claiming to be truth which does not come down from, nor have recourse to, Christ and that which He has revealed to us is, by definition, not truth.

- If Christ is Light (Truth) and Life, and Light has no communion with darkness (falsehood), then falsehood cuts us off from the Source of Life.

- Because the Church is in a relationship of direct communion with Christ, she has the Mind (Gr: Phronima or φρόνημα) of Christ. By this she distinguishes light from darkness, truth from falsehood, and proclaims these things authoritatively [Mt. 18:18; Jn. 16:13]. It is for this reason that she is the pillar and ground of Truth.

The Orthodox look at God and how we interact with Him in a radically different way than do the Western Confessions—both Catholic and Protestant. It often surprises people to learn that Protestants and Catholics are far more similar than either is to Orthodoxy. There is a passage in a novel by Eugene Vodolazkin, called Laurus, which highlights the difference between the God of East and West in a rather simple and beautiful manner. While passing through Vienna on his way to Jerusalem, the tales’ medieval Russian protagonist, Arseny, is speaking to his departed wife about the St. Stephen’s (Catholic) Cathedral:

“On the one hand, there is the sense of something kindred because we have common roots. On the other hand, I do not feel at home here: after all, our paths diverged. Our God is closer and warmer, theirs is higher and grander.” —Eugene Vodalazkin; Laurus, p. 239

This difference is perhaps summarized by the different theological conceptions represented in the dome and steeple of the respective churches.

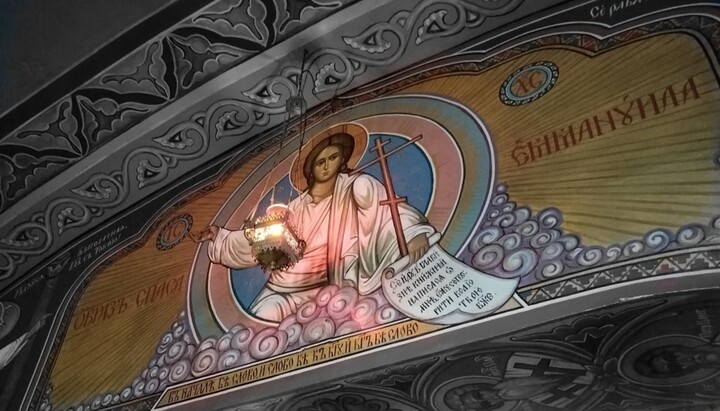

The dome of our Churches and the internal arrangement is designed to present God as immanent, a Divine Person who, in spite of being unknowable and infinite in His essence, is among us. The onion domes of our own Russian Church represent the tongues of fire descending at Pentecost, the outpouring of the Holy Spirit upon the Earth. The iconography in the church’s interior begins at the ground level with trees, vines, flowers; these lead into biblical scenes and saints—our fellow church members—gradually leading us upwards. All are ultimately pointing to Christ, who appears both amongst us in the biblical scenes, and above us as the Almighty (Gr. Pantocrator or Παντοκράτορας).

By contrast, the steeple is designed to draw the eyes up towards the heavens—its taper is designed to further emphasize the distance—to a God high above who is unreachable by man. Biblical scenery is usually reduced to a bloodied Christ on the Cross. Everything is designed with a grandeur meant to emphasize the inaccessibility of the Divine Essence—contrasted only by the bloodied God-Man, tortured in our place before again ascending to inaccessibility. For the Orthodox, God is a Person, and the highest communion with God comes through active participation in His Life and Activity with one another. For the West (both Catholics and Protestants) God is Essence, known only through intellect. This creates a sense of man being not only distant from God, but autonomous.

If God is known only through intellect, then reading or studying texts about God becomes the primary means by which we attain salvation. We see this clearly in Protestantism, where being able to directly quote a specific chapter and verse of Scripture verbatim is the highest form of piety. We see it manifest in Catholicism through Scholasticism and the many great naturalists, scientists, legal scholars, et al, of the Catholic tradition.

And let us be clear: it’s not that studying these things are bad in of themselves (God forbid), but when detached from praxis, from the experience of God, they become little more than speculative, subjective rationalizations detached from their transrational origin in the Person of Christ. This is precisely why in both Catholicism and Protestantism, the hyper-intellectualism at their core is often rebelled against by sensualist mystics— such as Catherine of Siena, Marguerite Porete, Pentecostalism and Charismaticism.

The American Mind

All categories of understanding, methods of analysis, interpretation and formulation of presuppositions are ultimately rooted in the principles underlying the surrounding society. We have to recognize that our own intellectual sensibilities are shaped by the worldview peculiar to the culture and society in which we exist and that we have inherited this worldview as the default lens through which to determine the truth of a thing. In our case, that worldview is rooted in a base materialism, skepticism, ethical nominalism and dialectics. And so, we bring these things to the Scriptures and the Church and must recognize that any allusion to a plain reading of Scripture is no more than self-deception. We are like the Ethiopian trying to read the prophecy of Isaiah whom the Apostle meets and asks, “do you know what you’re reading?” and we must respond in unison “how can I if no man should teach me?”

The first step to conversion is recognizing that we too need some man to teach us. We should approach the church and listen to her teachings with humility and childlike simplicity. If we hear a teaching that makes us uncomfortable based on our prior understanding then our assumption should not be that the Church is wrong, but that our prior understanding is wrong and we still have much to learn. The Orthodox faith does not fall into the traps of Western dialectics and we must keep this in mind when something seems to “contradict” our previous understanding.

Without this, our worldview—and the worldliness which comes with it—lead us to many temptations:

- Arguing with the priests or teachers about the teachings of the Church.

- Setting ourselves up as teachers.

- Attempts to peel off doctrines and practices which our American worldview finds objectionable.

- Pridefulness, self-assurance that we know better.

If we truly want to be Orthodox, if we are serious about dying to the world and living in Christ, we must shed this American Mind, and take on the Mind of the Church, an Orthodox Worldview.

Purification, Illumination, Deification

Acquiring the mind of the Church is no small task. It is not something we acquire simply through initiation into the Church. Nor is it a set of principles one can learn and by which one can judge others in the Church or events in the world. Instead, it takes a true appropriation of the Gospel in mind and heart, in word and deed.

We see it manifested, for example, in the oneness of mind between the hundreds of bishops from as far and wide as Britain, the Balkans, Ethiopia, Persia, and India who came together and proclaimed the same faith at the Council of Nicaea. Likewise, we see the Orthodox phronima reflected down through the centuries in the lives of the saints: in the continuity of their teachings, the sanctity of their lives, and their superabundant love for the whole of creation. Looking at the lives of saints, we see the Apostolic way of live clearly linked from generation to generation to our own day. Likewise, if we wish to acquire the Mind of the Church we must read and imitate the lives of the saints and call on them for help in moments of weakness.

There are no shortcuts. The acquisition of the Orthodox worldview occurs over a number of years through our participation in the Life of the Church—its sacraments, liturgical cycles and ascetical exercises. By entering into the life and activity of the church, we enter in the life and activity of Christ. As we participate in this life, the Lord cleanses us not only of the sins we’ve committed, but of the passionate inclinations towards sin. Being Purified from our sins and passions, our hearts are softened, our minds are Illumined so that we may “perceive wondrous things out of [His] Law”[Ps. 118:18 LXX].

Put more simply, as we grow in grace, as we progress in our relationship with God, He reveals things about Himself to us just as any loved-one does. This spiritual ascent, this vertical progress is what we should aim for, and is why it's crucial to read the Lives of the Saints—the lived theology of the Church.

“To have an Orthodox Mind, one of the key things is to have a sense of humility and that you don’t know everything.” —Fr. John Whiteford

Convert Pitfalls: Intellectualism & the Correctness Disease

The Western Mind with which new converts come to the Church leads them to easily fall prey to an over-intellectualization of Orthodoxy. Because of the rampant sectarianism of the West, we come to Orthodoxy and want to learn all the doctrines as quickly as we can, believing that this will make us Orthodox. This robs Orthodoxy of its power, reducing it to little more than an ideology.

If we are not living an Orthodox Life, not acquiring an Orthodox heart, then we are not Orthodox—regardless of the correctness of our “beliefs.”

By mistaking this horizontal progress for the acquisition of the Mind of the Church many fall quickly into what Fr. Seraphim Rose called the Correctness Disease.

This is an obsession with the letter, an over rigorous attitude in which we become so “orthodox” that we stick our noses up at the babushka who venerates an icon in the presence of the Eucharist, or the icons before the Cross after the dismissal; we feel we know more than our teachers, priests, and even bishops, and argue with them lacking even the shadow of Christian love and charity. We assume everyone is a heretic and engage in endless arguments of doctrine, setting ourselves up as apologists and teachers—forgetting the warning of the Apostle James.

The cure to the Correctness Disease is humility.

The cure to the Correctness Disease is to live an Orthodox Life. If you are being obedient to your priest, praying your prayer rule, reflecting on your sins and struggling against them, fulfilling the obligations the Church has set forth and by which saints have been sanctified for twenty centuries, you will attain the Pearl of Great Price.

Now, I am not saying that we shouldn’t read the Scriptures, the Church Fathers, etc… We should. But we must remember the words of Christ: “You search the Scriptures, for in them you think you have eternal life; and these are they which testify of Me” [Jn. 5:39]. We must remember that Truth is a Who, not a what.

Saint Maximus the Confessor, himself one of the most profound theologians in the history of the Christian Church, has this to say in his commentary of the meeting of the woman at the well:

“Jacob’s well is Scripture; the water is the knowledge that scripture contains; the depth of the well is the meaning of the biblical enigmas which are all but beyond one’s reach. The bucket used for drawing out the water is ordinary learning which the Lord did not require since He is the Word Himself and he does not give this knowledge to the faithful through knowledge and study; but to those who are worthy He grants a measure of the ever-flowing wisdom of spiritual grace. Through ordinary learning, like the bucket, the soul receives only the smallest part of knowledge, letting go of the whole which no mind can grasp. But the knowledge which comes from grace contains, without study, the whole of wisdom that man can possibly contain, which bubbles forth in a variety of ways with a view towards his needs.” —St. Maximus the Confessor

Saint Maximus lived a life of deep prayer and devotion to God and because of this, the Lord opened up the Scriptures and Cosmos to him. The same is true of Saints Basil the Great and Gregory Nazianzus, who were some of the most educated men in all of Antiquity. Yet they spoke of the knowledge of God and the meaning of Scripture as being a gift (energeia) of God which He bestows upon the faithful who seek Him in truth and love. For the Church Fathers then, and for us, theology cannot be divorced from praxis, and comes forth from the mystical experience of God. This experience, or Vision of God (Gr. Theoria or Θεωρία) is an internal illumination which leads to an experiential knowledge of God (Ru. Bogopoznanie or Богопознание). Without this, we may skim the surface, but will never reach into the depths of God’s knowledge.

“A Theologian is he who prays Truly; he who prays truly is a theologian.” —Evagrius of Pontus

Convert Pitfalls: False Spirituality & False Humility

We must simultaneously watch out for the other common pitfall among converts, which is largely the opposite end of the spectrum: False Spirituality and False Humility. The ease of availability of the most advanced of spiritual texts, such as the Philokalia, the works of St. Gregory Palamas and St. Symeon the New Theologian, leads inevitably to catechumens trying to read these texts and practice the rigorous ascetical exercises and exalted states of prayer they describe. Failing to grasp their own spiritual poverty and the schemes of the demons, they are led into false states of ecstasy, demonic visions of light, etc... This is extremely dangerous. There are several cases in which Americans have fallen into madness and had to be institutionalized.

“It is all very well to have reverence for the great saints who have actually lived it; but unless we have a very realistic and very humble awareness of how far away all of us today are from the life of hesychasm and how little prepared we are to even approach it, our interest in it will be only one more expression of our self-centered, plastic universe. ‘The me-generation goes hesychast!’ — that is what some are trying to do today; but in actuality they are only adding a new game called ‘hesychasm’ to the attractions of Disneyland.” —Fr. Seraphim Rose

This error and that of false humility/false piety occurs largely among those of puritanical/pietistic backgrounds. Often, converts will feign piety and humility outwardly, believing that because they don’t struggle with a particular passion (such as alcohol) or engage in a particular activity which may be seen as questionable (such as attending a non-christian concert) that they are more pious than others, even gossiping about them, all the while saying “well I’m no one, I’m just a sinner.” The internet has made this temptation particularly common among young converts.

This is pharisaism, hypocrisy.

We don’t know the hearts of others and when we judge, we usurp the throne of God, the one judge of all. The Pharisee, if we remember, kept the fasts, prayed at all the hours of prayer, but his pride and judgement of others meant that he left the temple still in his sins. By contrast, the Publican judged himself the worst of men, wept over his sins and left justified. We should seek true humility. This starts by honest reflection on our sins and obedience to our spiritual fathers and confessors. Remember that the priest is like a doctor for our souls. By being open with our priests about our temptations, letting them guide our prayer rules and fasting, we ensure that we get the medicine we need when we need it.

Humility: A good litmus test for our pridefulness is how we look at Judas. If we look at Judas with disdain or as fool who is below us, we are prideful and on the road to prelest. If we weep for Judas, if we want to ask the Lord to forgive him because “Judas betrayed Thee but once, O Lord, but I betray you each and every day of my life,” then we are moving in the right direction.

"The point is—and it is a point that is absolutely necessary for our survival as Orthodox Christians today—we must realize our situation as Orthodox Christians today; we must realize deeply what times we live in, how little we actually know and feel our Orthodoxy, how far we are not just from the saints of ancient times, but even from the ordinary Orthodox Christians of a hundred years or even a generation ago, and how much we must humble ourselves just to survive as Orthodox Christians today.” —Fr. Seraphim Rose

Conclusion

Fr. Alexander Logunov often says that it takes ten years in the Church to really become Orthodox—to acquire the Mind of the Church—and there is certainly merit to this. No amount of reading can bestow it upon a convert, it is gained through years of struggle, years of participation in the life of the Church. Why wouldn’t it? We have spent our whole lives in a secular rhythm, it will likewise take years in the rhythm of the Church for it to become an organic part of ourselves and to bear its fruit. We must, in the meantime, not enclose our minds in mere knowledge of the faith, but struggle against the passions, always tamping down our desire to judge others and see ourselves as the measure of Orthodoxy.

To acquire an Orthodox Mind is to enter into the liturgical, ascetical, and sacramental life of the Church in patience and humility. Our roadmap is the Lives of the Saints, wherein we see the Gospel lived—the Acts of the Apostles continued on from generation to generation.

Orthodoxy is a marathon, not a sprint.

You will see periods of great zeal, but also of great spiritual dryness and struggle. But through repentance, patient endurance, and relying on more mature Christians in your community, you will endure and in time acquire the Mind of the Church. Orthodoxy is reality in its fullness; it is reality as it truly is, not merely as it appears to be. To be Orthodox means to be properly oriented towards God, our fellow man, and the entire created world. In the Church, we learn to see our Lord Jesus Christ in everything and everyone.

Let this be the measure of your faith.

Originally posted to Where the Wasteland Ends