What I Have Always Believed

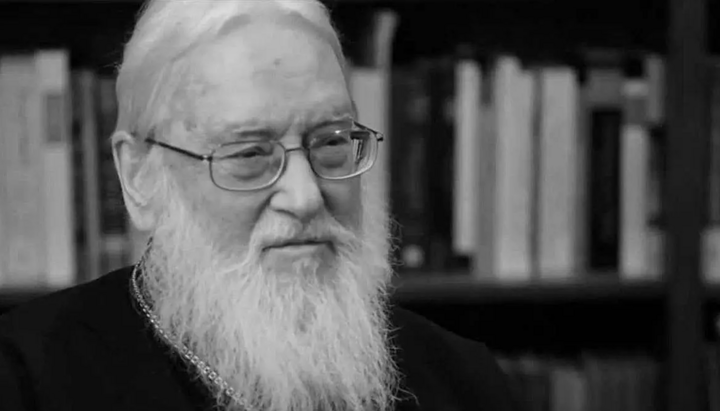

Kallistos Ware is a towering figure in the renaissance of Western Orthodoxy. Recently, St. Vladimir's Seminary Press published the first two volumes of his collected works. They do not disappoint.

At the beginning of our family’s journey towards Holy Orthodoxy, I asked a Uniate priest to recommend a book on the Eastern Christian tradition. He gave me a copy of The Orthodox Church by Timothy Ware. My wife thinks of this as my “point of no return.” After reading Ware’s book, Orthodoxy went from a mere interest to a conviction, an obsession, a love.

That may seem odd, given its “academic” tone. Yet I’ve met dozens of converts who have shared my experience: Once they read The Orthodox Church, they were hooked. There was no going back. I heard this, most recently, from a professional basketball player who is now a catechumen at our parish.

What is it about Ware’s book? After several years and many re-readings, I think I have the answer.

Ware was twenty-four years old when he converted to Orthodoxy. Two years later, at the urging of Penguin Books, he began to write The Orthodox Church. The book was published a few months shy of his thirtieth birthday.

It’s clear that, when he wrote The Orthodox Church, Ware was a “zealous convert.” Unlike many of us, however, his zeal was completely innocent. He had no desire to put down Catholics or Protestants; he had no taste for Church politics. His enthusiasm was directed completely towards its proper object, the Orthodox Church: its history, theology, and spirituality.

As it happens, Ware didn’t want to write The Orthodox Church. Penguin Books, the most respected publisher in the world, approached the young Ware asking him to pen an introduction to Orthodoxy. At first he declined, feeling himself too young and inexperienced (a good instinct!). A mentor urged him to give it a shot, however. And so he did.

This modesty, I think, also comes through in Ware’s book. His great love for the subject is tempered by his natural humility. Of course, his own personality—gentle, kind, bookish—can’t help but shine through. Yet this is a strength rather than a defect. It makes the book more compelling, because the author himself is so endearing.

Mr. Ware never lost this spirit, even as he rose through the ecclesiastical ranks. In 1966, he was ordained to the priesthood and received the monastic tonsure, taking the name Kallistos. In 1982 he was consecrated a bishop, being named Metropolitan of Diokleia.

In addition to his duties as a pastor and professor (he taught at Oxford for more than three decades), Kallistos continued to write. He authored, coauthored, edited, or translated fourteen books. He also penned countless articles, essays, prayers, many of which are now being collected by St. Vladimir’s Seminary Press. So far, SVSP has released the first two volumes: The Inner Kingdom and In the Image of the Father.

Volume one contains, among other gems, Ware’s conversion story. In 1950s Britain, the idea of an Englishman joining the Orthodox Church was unheard-of. In fact, when he first asked the local Greek bishop to receive him into the Church, he was told to remain in the Anglican Church! The bishop was afraid he would feel an outsider in a Church that was, at that point, made up entirely of Greeks. Besides, at the time, prospects for Orthodox-Anglican were so strong that folks like Ware were encouraged to remain within the Church of England, to serve as “an ‘Anglo-Orthodox’ leaven,” as he calls it.

Ware’s first encountered Orthodoxy during a chance visit to St Philip’s Church on Buckingham Palace Road in London. Ware had never met an Orthodox Christian prior to that day, nor did he know anything about the Orthodox faith. He simply saw the little sign that said “Russian Church,” was intrigued, and went inside. “As I left the Church,” he recalls, “I said to myself with a clear conviction: This is where I belong; I have come home.”

This is a sentiment with which many of his fellow converts would agree. Another is this:

The more I learnt about Orthodoxy, the more I realized: this is what I have always believed in my inmost self, but never before did I hear it so well expressed. I did not find Orthodoxy archaic, foreign, or exotic. To me it was nothing other than simple Christianity.

These collections also contain some of Ware’s very best academic-theological essays on the Philokalic tradition. Volume two, for example, reproduces his well-known essay “Prayer in Evagrius of Pontus and the Macarian Homilies.” In this critical work, Ware explains why on the one hand the Orthodox Church has never fully embraced Evagrius, while on the other—and despite these reservations—he remains a critical figure in Orthodox spirituality.

Ware notes the distinct influence of Origenism upon the Pontian’s writings. This influence occasionally manifests itself in an unhealthy dualism. At times, Evagrius not only distrusts the body (which is good) but scorns it (which is not). He treats it as an obstacle in the soul’s path to illumination. Macarius has a more balanced view. He treats the body as the soul’s partner, rather than its enemy. Soul, mind, and body cannot achieve theosis separately or individually. They must be divinized together, or not at all.

Nevertheless, Ware has a deep and sincere appreciation for Evagrius. “Instead of saying either/or,” he writes, “let us say both/and”—that is, both Evagrius and Macarius, together:

The two “currents” they represent should be seen as complementary rather than mutually exclusive; a balanced theology of prayer has need of both of them. Evagrius requires to be “de-Platonized” and incorporated in a framework that is more Christocentric in its basic vision and more holistic in its anthropology; his clarity and precision need to be suffused with the affective warmth of the Macarian Homilies. But at the same time the enthusiasm of Macarius needs to be moderated by the more systematic approach of Evagrius.

This balanced view is what Ware calls the “Byzantine synthesis,” and it is extremely representative of his theological style. Ware’s aim here is not merely to show off his education, nor to pit one mystic against the other in a kind of intellectual blood-sport. It is, rather, an effort to show how the Fathers, despite their differences, share the same fundamental understanding of Man and his relationship with God.

It should be noted that, over the course of his life, Ware’s views did change, sometimes quite radically. In his second book, Eustratios Argenti, Kallistos implicitly argues that Catholics and Protestants who convert to Orthodoxy ought to be received via baptism. Yet, by the end of his life, he would not even refer to such people as converts, because (as he put it) “conversion is to Christ, not from one Christian community to another.”

In 2018, Fr. Lawrence Farley wrote: “As well as following his upward path of ecclesiastical promotion, I have also followed what I consider to be his downward path away from Orthodox Tradition—or at least from his own formerly-held positions.” This is difficult to hear. Unfortunately, however, Fr. Lawrence speaks for many of Kallistos’s admirers who looked on, bewildered, as he softened his position on critical issues such as contraception, women’s ordination, and homosexuality.

Still, we can be confident that this will not be Ware’s legacy. That is, he will not be remembered as a “liberalizing" force in the Orthodox Church, but as a pivotal figure in the renaissance of Western Orthodoxy. He is a giant, and virtually every convert in the English-speaking world stands on his shoulders. St. Vladimir's Seminary Press is doing a great service to the whole Church by making these lesser-known writings more widely available.

May God remember His servant Kallistos forever in His kingdom! In the meantime, I hope we can look forward to many more volumes of the "Collected Ware" from St. Vladimir's Seminary Press.